As we live through the rapid change of our contemporary culture, some are fearful that Christianity is losing its traditional, privileged place. Demographers tell us that the fastest growing cohort is the so-called “nones,” those with no religious affiliation or particular religious practice. Those who are fearful about this development warn that the lost, privileged place of the Church’s faith will inevitably lead to a growing hostility toward Christianity. Every fear has at least a kernel of truth to it, so there’s reason for us to pay attention. But I don’t think fear about the changing nature of the culture is a faithful response, even as we pay attention to it. Fear is never faithful. All culture is highly elastic and, at least partly, cyclical. Historians look back and find times when particular social, religious, political, and economic conditions in one era were similar to those in another. That’s true of Church history as it overlaps with the larger cultural history. In every age then, the Church faces new as well as familiar challenges for how she will be faithful to the Gospel of Jesus.

I believe we’re in a similar time as to what the Church experienced in the 4th Century. Christianity then had a foothold in the culture, but it was by no means the dominant religion. The Roman Empire had grown vast, outgrowing its own power to govern and control that vastness. In the other words, the Pax Romana wasn’t what it had been. This resulted in great social anxiety as groups sought to blame other groups for why Rome wasn’t what it used to be. Some blamed the Christians. Others blamed the laxness of the traditional Pagan practices. What was evident was this: No one group was dominant or privileged in its ability to guide the culture. This was also the time of the great Church Councils of Nicea and Chalcedon. At these Councils, the Church struggled to define her own faith, identity, and practice. But even amidst the great debate within the Church, we continued to witness to the grace, compassion, and mercy of God. In the middle of the 4th century the Roman emperor Julian (later he had the moniker “the Apostate” attached to his name, which, let’s just say, wasn’t a term he chose) wrote a sarcastic complaint about the Christians he observed: “These impious Galileans not only feed their own poor, but ours also. While our pagan priests neglect the poor, these hated Galileans devote themselves to works of charity.”

The Church today is struggling, as we always have, to live out our faith, identity, and practice. As was true 17 centuries ago, today we’re not all of one mind on various issues. But that has never stopped the Church from its essential witness to the world’s redemption by our Lord Jesus Christ. We’ll need to continue to find ever more creative and effective ways of sharing and dispensing God’s grace to this beautiful, yet broken world, especially as it becomes more disinterested in or indifferent to the Gospel. So, I believe the truth claims we make about Jesus will never win the day if they’re limited to a “we’re right and your wrong” contest. I think the Emperor Julian (the Apostate) unwittingly showed us the most effective way: A steadfast commitment to sharing God’s unmerited grace with others, particularly to those who are lonely, lost, or left out in our culture, through specific acts that make tangible God’s grace in their lives. The old camp song has it so right: “They will know we are Christians by our love.”

+Scott

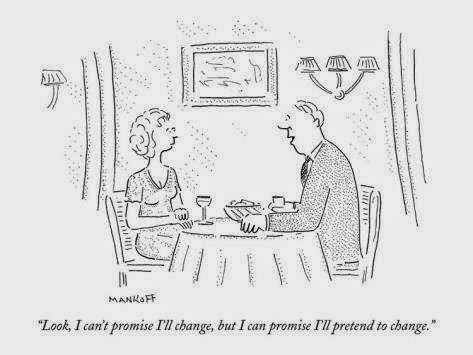

Change is hard. We resist

Change is hard. We resist The Rt. Rev. Scott Anson Benhase was the tenth Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia from 2010-2020. This website serves as an online archives for the weekly email reflections, the eCrozier, he wrote during his episcopacy.

The Rt. Rev. Scott Anson Benhase was the tenth Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia from 2010-2020. This website serves as an online archives for the weekly email reflections, the eCrozier, he wrote during his episcopacy.