Pride, as we know, is one of the Seven Deadly Sins. It celebrates the self and the self’s accomplishments over others and their accomplishments. In extreme form, pride places the self above God and what God’s accomplished in our creation and in our redemption in Jesus. Even so-called “self-help” can be a form of pride. Books published with the moniker “Christian self-help” are really no help (“Christian” and “self-help” in the same sentence should give us pause). Such books approach sin as if we can cure it by faithfully working harder. But there’s no self-cure for sin. Yet, we think we can balance our pride with a healthy dose of modesty, limiting ourselves to a humble satisfaction and only a diffident delight in who we are and what we’ve done. From my experience, such a balancing act ends up being self-delusional. In his poem, Jordan II, George Herbert tries to pen a poem celebrating God, but gives up when he realizes the object of the celebration is himself (“So did I weave my self into the sense”). Even our efforts that seem selfless can end up serving our self-aggrandizement. He writes:

When first my lines of heav’nly joyes made mention,

Such was their lustre, they did so excell,

That I sought out quaint words and trim invention;

My thoughts began to burnish, sprout, and swell,

Curling with metaphors a plain intention,

Decking the sense, as if it were to sell.

Thousands of notions in my brain did runne,

Off’ring their service, if I were not sped:

I often blotted what I had begunne;

This was not quick enough, and that was dead.

Nothing could seem too rich to clothe the sunne,

Much lesse those joyes which trample on his head.

As flames do work and winde, when they ascend,

So did I weave my self into the sense.

But while I bustled, I might heare a friend

Whisper, How wide is all this long pretence!

There is in love a sweetnesse readie penn’d;

Copie out onely that, and save expense.

Balance, in this way, isn’t at all helpful for me. The only help is my clear-eyed, full-hearted (Coach Taylor on Friday Night Lights!) acknowledgment of the mixed bag sinner I am. Seeking a balance between selfishness and selflessness is a dead end (or between greed and generosity, or envy and admiration). What is helpful is an unfiltered honesty about myself, mixed bag sinner that I am. As Herbert concludes in Jordan II, God’s love for us is a “sweetnesse readie penn’d.” It’s the “onely” cure. All else will delude us into believing that we can strike a balance between our sinfulness (say 49% of the time) and a more faithful life (say 51% of the time). It’s Sisyphean. It’ll produce in us an all-encompassing exhaustion rather than set loose in us the liberation of grace.

+Scott

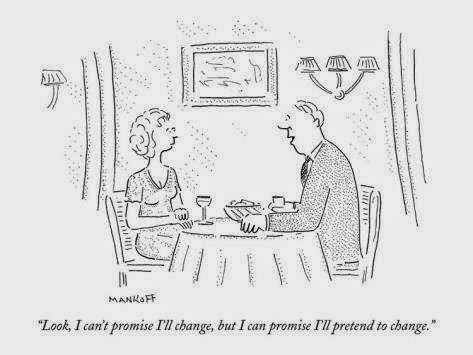

Change is hard. We resist

Change is hard. We resist The Rt. Rev. Scott Anson Benhase was the tenth Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia from 2010-2020. This website serves as an online archives for the weekly email reflections, the eCrozier, he wrote during his episcopacy.

The Rt. Rev. Scott Anson Benhase was the tenth Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia from 2010-2020. This website serves as an online archives for the weekly email reflections, the eCrozier, he wrote during his episcopacy.